To walk through the stone corridors of Old Montreal in the depths of January is to engage in a form of urban archaeology. As I stood at the Old Docks, the St. Lawrence River was no longer water but a vast, tectonic plate of ice, a reminder that for the French pioneers of the 17th century, this was not just a scenic vista, but a biological prison. For five months of the year, the social code of New France was physically sealed off from the rest of the world, creating an isolated laboratory of human interaction and survival.

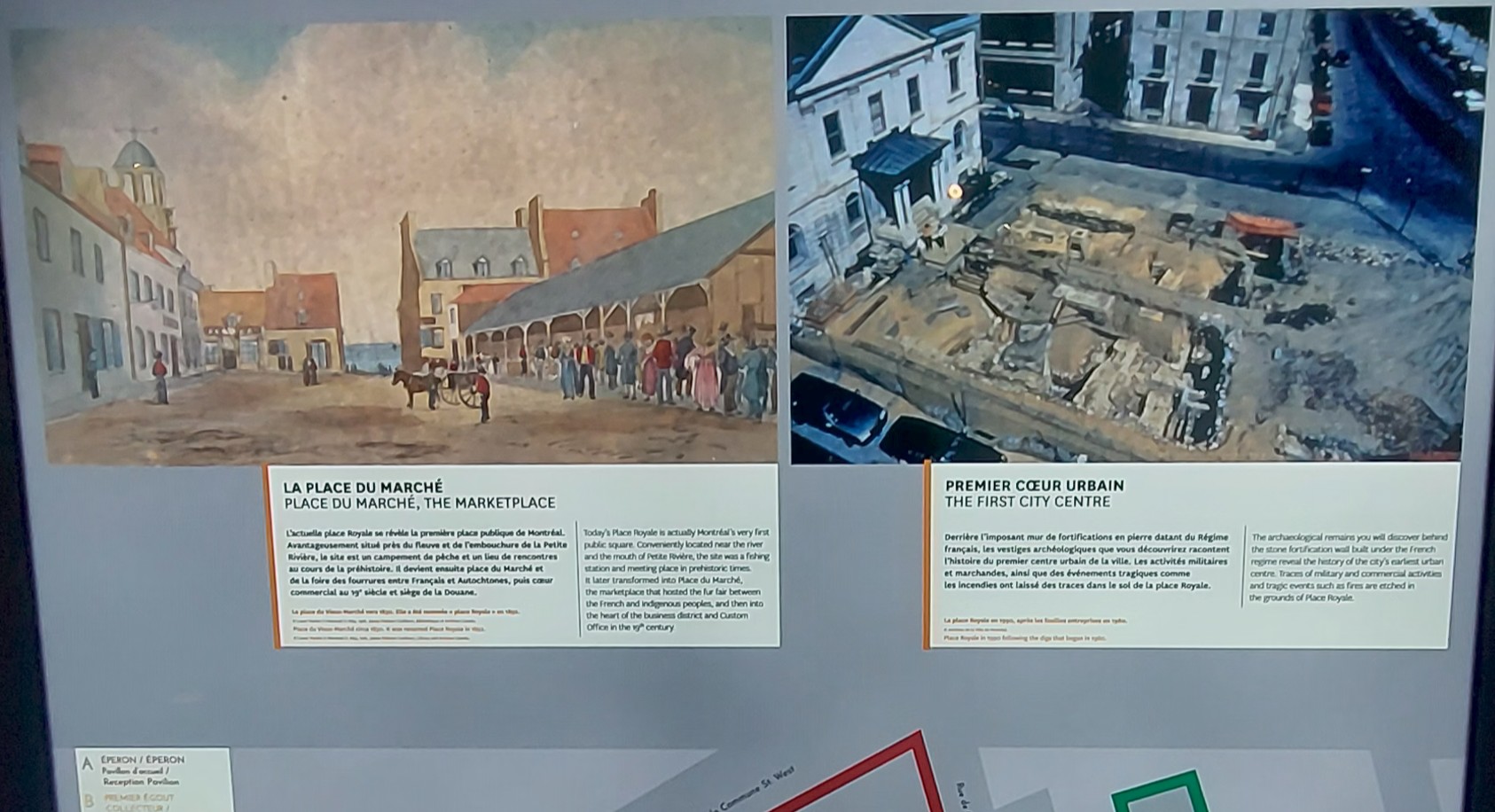

The true genesis of this city, however, does not lie in the grand facades above ground, but in the damp, silent spaces beneath the pavement. At the Pointe-à-Callière, the museum of archaeology and history, I descended into the very earth where Montreal was born as Ville-Marie in 1642. Walking through the excavated remains of the original Fort, one can see the literal foundation of the French mission. It is here that the interaction between the French pioneers and the Indigenous populations becomes more than a historical footnote; it becomes a physical reality.

The soil reveals a complex narrative of co-dependence and collision. The French arrived not as conquerors in the traditional sense, but as religious zealots aiming to build a utopian missionary city. Yet, the archaeological record shows that they built their fort directly upon the ancestral sites of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. This was a re-occupation of a space that had been a crossroads of Indigenous trade for millennia.

In the underground site of the first cemetery, one can observe a poignant truth: the remains of French settlers and Indigenous converts lie in the same consecrated earth. It serves as proof that the “conversion” was not just spiritual; it was a total immersion of two cultures trying to navigate a landscape that was indifferent to both.

Emerging from the dark, cold origins of the fort and stepping into the Notre-Dame Basilica is a transition into a different kind of observation. If the underground represents the raw, desperate struggle for survival, the Basilica represents the triumph of the institutional ego. Completed in the 1820s, its blue-vaulted ceiling and gilded stars were designed to mimic the heavens, a deliberate architectural attempt to dwarf the individual.

As a witness to this space, I noticed how the interior light—a soft, filtered indigo—contrasts sharply with the blinding, aggressive white of the snow outside. It was a space designed to convince the convert that the “Order” of the Church was more powerful than the chaotic, frozen wilderness of North America.

Walking back toward the old docks, past the massive ships and the weathered stone of the 19th-century warehouses, the persistence of the city becomes clear. Montreal is a city of layers; every street is a document that has been erased and rewritten. The French pioneers intended to build a sanctuary for souls, but the geography of the river turned it into a machine for trade. The frozen river I observed is the same one that Cartier hoped would lead to China, but which ultimately led to the industrialization of a continent. To see these layers—from the mud of the original fort to the towering spires of the 1800s—is to understand that a city is never finished; it is simply a continuous attempt to impose a human structure upon a landscape that remembers everything.

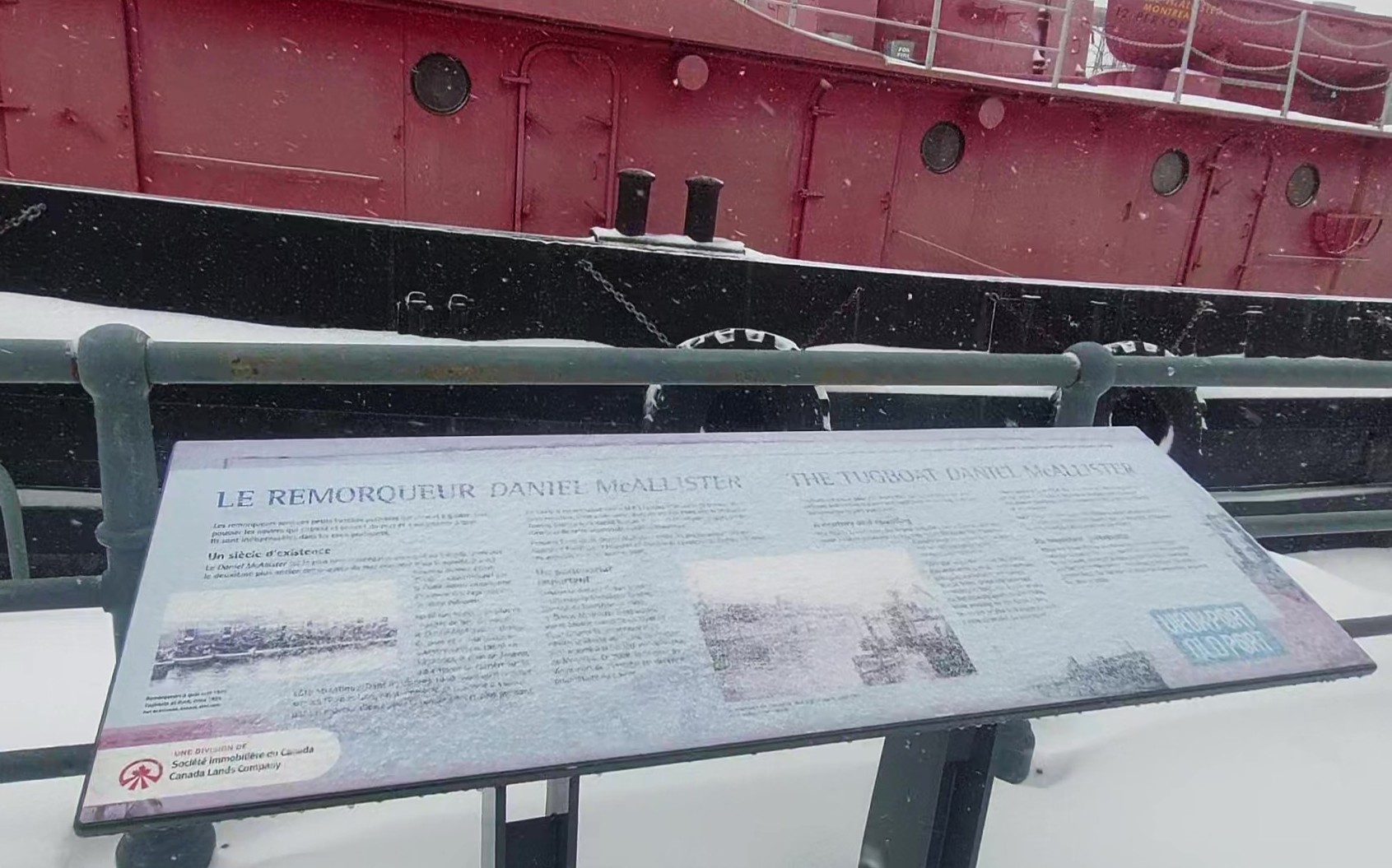

The presence of the Daniel McAllister at the entrance of the Lachine Canal serves as a formidable steel witness to the era when Montreal transitioned from a religious mission into the industrial engine of North America. Built in 1907 and originally christened the Helena, this vessel is a rare survivor of the golden age of steam and diesel, holding the distinction of being the largest preserved tugboat in Canada. To look at its heavy, utilitarian hull today is to see the mechanical evolution of the “Social Code” on the St. Lawrence River—a shift from the spiritual navigation of the Jesuits to the raw, industrial navigation of the 20th century.

During its prime, the Daniel McAllister was the essential muscle of the port, tasked with the high-stakes labor of guiding massive grain barges and ocean-going ships through the treacherous currents and the narrow, unforgiving confines of the canal. The sheer power required for this task is evident in its construction; in 1946, the vessel was completely refitted with a massive diesel engine to keep pace with the increasing scale of global trade. This boat did not just exist in Montreal; it actively built the city’s economic prominence, working the docks until the 1980s and witnessing the rise and fall of the industrial waterfront.

There is a profound historical irony in the boat’s current resting place near the Old Port. While the nearby Notre-Dame Basilica was engineered to draw the eye upward toward the divine, the Daniel McAllister was engineered to pull downward into the dark, heavy reality of the river’s resistance. It represents the “Worker’s Code”—a philosophy of torque, steel, and relentless persistence. Unlike the French pioneers who sought to convert the landscape, the crews of this tugboat sought to conquer it through engineering and grit. Today, as it sits motionless in the very water it once dominated, the boat serves as a forensic link to the thousands of laborers whose lives were dictated by the rhythm of the tides and the demands of the canal. It remains an vital piece of the Montreal narrative, proving that the city’s foundations are built as much on the soot of the engine room as they are on the incense of the altar.

The juxtaposition of these two extremes—the humid, ancestral resistance of the Afro-Brazilian Museum in São Paulo and the subterranean, frozen foundations of Montreal—reveals the global architecture of the social code. Only a few days prior to walking the icy docks of the St. Lawrence, I was immersed in the history of the Quilombos and the deep, resilient narratives of the African diaspora in Brazil. In São Paulo, the museum stands as a testament to a culture that refused to be erased, preserving the spiritual and physical artifacts of those who were forcibly brought across the Atlantic. It is a space defined by the heat of persistence and the vibrant, unyielding memory of a people who built their own sanctuary within a hostile empire.

Stepping from that tropical intensity into the -10°C reality of Montreal creates a profound analytical friction. While the Afro-Brazilian narrative is one of survival through the preservation of African identity against the Portuguese machinery of labor, the Montreal narrative is one of a French attempt to transplant a European Catholic identity into a landscape that was already ancient. In Brazil, I observed the social code as a tool of exclusion and resistance; in Canada, I saw it as a tool of conversion and cold, industrial persistence. Both locations, however, are anchored by the same human necessity: the struggle to claim a piece of the earth and define it as home.

As a witness who has crossed 40 degrees of temperature and four time zones in a single week, I see these cities not as isolated destinations, but as chapters in the same global ledger. The Daniel McAllister tugboat and the sacred artifacts of the Quilombos are different dialects of the same language that refuse to be moved by the currents of time. I return to the coal-rich soil of Bytom with these two worlds colliding in my memory: the sun-drenched resistance of the south and the frozen altars of the north. They serve as proof that whether we are building a mission in the snow or a community in the jungle, the human spirit is always searching for a way to write its own story over the landscape, leaving behind forensic scars for the next observer to decode.