The contrast between the Island of Paquetá and Ilha da Gigóia offers a profound forensic study in the spatial manifestation of human intent. To the uninitiated, both are simply car-free sanctuaries within the Guanabara and Marapendi waters. However, to the Sovereign Witness, they represent two divergent philosophies of the moat, one designed for the preservation of status, and the other for the tactical evasion of urban invalidation.

Paquetá is a landscape of presumption of intent frozen in the 19th century. Strategically located in the heart of Guanabara Bay, its purpose was never merely residential; it was a curated stage for the Imperial elite. As I walked past the rusted cannons and the hollowed remains of the abandoned schools, I was observing the “Forensic Scar” of a social project that has outlived its architects. The island’s strategic value in the 1800s was its proximity to the seat of power in Rio, coupled with its maritime isolation which allowed for a controlled, sanitized reality.

Sources suggest Paquetá was once the most technologically advanced retreat in the Empire. Today, however, that progress has turned to stagnation. The silence there is heavy—a byproduct of a world that was built to be a monument. The lack of cars is not a modern eco-conscious choice, but a remnant of a time when the pace of life was dictated by the horse-drawn carriage and the steamship. In Paquetá, the Witness observes a history that has stopped breathing, preserved like an artifact in a salt-crusted display case.

Crossing the Marapendi Lagoon to Ilha da Gigóia reveals a startlingly different forensic timeline. If Paquetá is an artifact, Gigóia is a metabolism. Its strategic location—hidden in the mangroves of the West Zone—was not chosen by Emperors, but by those seeking a sovereign refuge from the aggressive urbanization of the 20th century. While the mainland of Barra da Tijuca was being partitioned into aggressive invalidation through high-rises and highways, Gigóia was growing in the shadows.

The data of Gigóia is found in the constant motion of the chalanas. Here, the purpose is not status, but the maintenance of a sovereign void, a place where the city’s logic of car-ownership and rigid zoning fails. Its narrow alleys are tactical; they are physically incapable of supporting the mainland’s chaos. In Gigóia, I observed an organic vitality where the residents have built a self-sustaining world through necessity. The silence here is not the silence of the grave, as in Paquetá, but the silence of a hidden frequency—a community operating on a different wavelength than the metropolis just five hundred meters away.

When we compare these two islands, we see the dual nature of the witnessed reality. Paquetá was a top-down imposition of order, while Gigóia is a bottom-up assertion of existence. The “Forensic Detail” that separates them is the material of their survival: Paquetá relies on the permanence of stone and the memory of the Crown, while Gigóia relies on the fluidity of the water and the constant adaptation of its wooden piers. During the colonial and early Imperial periods, Paquetá served as a strategic sanitarium, a place where the elite fled the aggressive invalidation of the mainland’s filth and disease. 19th-century Rio was a city of yellow fever and cramped colonial quarters; Paquetá was the antidote.Did you know that while one island was being fortified to protect a King, the other was being used to hide the very people the King sought to rule?

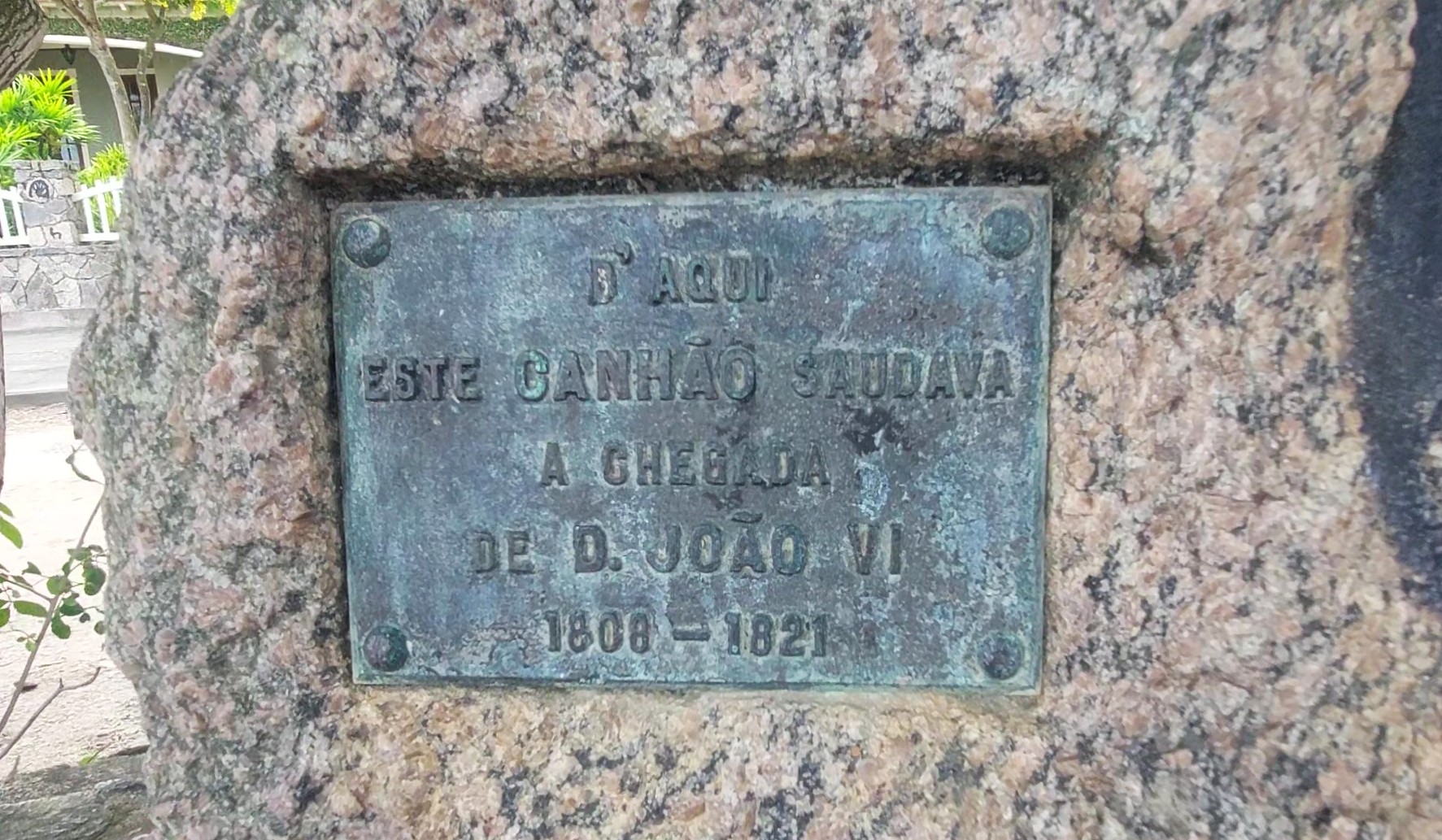

Data of the time identifies the island as a favorite of Dom João VI, who utilized it as a site of State Sovereignty. Life there was a performance of European etiquette adapted to the tropics. The big cannons you observed were not merely for defense; they were forensic markers of the island’s status as a protected enclave. The purpose was isolation for the sake of luxury. The enslaved population on the island was managed with a different aesthetic—they were the hidden labor force behind the manicured gardens and the stone villas, existing in a reality where their only trace was the physical endurance required to ferry the elite back and forth across the bay.

The purpose of living in the mangroves during colonial times was purely utilitarian. It was a site for Caiçara subsistence—a blend of Indigenous and European outcasts who survived on the data of the tides. Strategically, the island was a labyrinth. The dense mangroves made it an ideal location for those who did not wish to be processed by the colonial administration. It was a landscape of Tactical Invisibility.

While the elite in Paquetá were building stone foundations to announce their presence, the inhabitants of the Gigóia region were building with wood and thatch—materials that left a smaller forensic scar. They lived by the sovereignty of the swamp, utilizing the lagoon as a natural barrier against the tax collectors and the military drafts of the mainland.

- Paquetá was a Strategic Asset for the display of power. Its isolation was a privilege.

- Gigóia was a Strategic Shelter for the evasion of power. Its isolation was a survival mechanism.